For an appointment about pain, symptoms, risks, and treatments, contact us. To learn more about our world renowned surgeon at Seattle Neuroscience Institute, visit our home page.

Seattle Neuroscience Institute

- Home

- Conditions & Treatments

- Arteriovenous Malformation AVM

- Brain Aneurysm | Cerebral Aneurysm

- Carotid Artery Disease

- Cavernous Malformations

- Colloid Cyst

- Glossopharyngeal Neuralgia

- Hemifacial Spasm

- Meningioma

- Minimally Invasive Spine Surgery

- Moyamoya Disease

- Spinal Canal and Spinal Cord Tumors

- Transient Vertebrobasilar Insufficiency

- Trigeminal Neuralgia Treatment

- Research & Publications

- Practice Locations

- About

- Contact

Moyamoya

Moyamoya disease is a progressive disorder of the cerebral vessels, characterized by narrowing of the intracranial vessels as they emerge from the base of the skull. Moyamoya means ‘puff of smoke’ in Japanese, and refers to the look of the tiny vessels appearing on cerebral angiography in patients with this condition. Moyamoya disease is progressive and the underlying cause is unknown. The vascular narrowing process often begins one side, but true moyamoya disease inevitably progresses to involve the cerebral vessels on both sides. Patients usually present to medical attention in two distinct age groups.

One group of patients is first affected in childhood and the other group manifests initial signs and symptoms in adulthood. There are also two distinct clinical presentations. One group of patients

presents with intracranial hemorrhage, or bleeding into the brain. The other group of patients presents with stroke like symptoms with either transient ischemic attacks or with completed strokes. These strokes can either be deep in the brain, or they can be located in larger areas of the brain corresponding to arterial supply territories. Silent strokes can also be found in some patients at the time of initial presentation, and occasionally patients can present with decreased cognitive function. Occasionally headaches or seizure are the first clinical manifestation which lead to imaging studies. Brain infractions or hemorrhages most commonly occur in the cerebral hemispheres, but can also can occur rarely in the cerebellum.

The condition was first described in Japan, and much of the published literature describing the condition and what is known about it, has been published by Japanese investigators. It has subsequently been recognized that moyamoya disease is a cause of stroke and intracerebral hemorrhage in western as well as in Asian populations.

Symptoms

Typically, the first symptom of Moyamoya disease in children is often stroke, or recurrent transient ischemic attacks accompanied by muscular weakness, paralysis or seizures. Adults can experience either a stroke due to lack of blood supply or a hemorrhagic stroke (A,B) due to rupture of the fine brain vessels which form in response to the vessel narrowing (C,D).

Individuals with this disorder may have disturbed consciousness, speech deficits, sensory and cognitive impairments, involuntary movements and vision problems.

Causes and Risk Factors

Moyamoya does not have a specific cause, but is characterized by fibrotic narrowing of the large vessels at the base of the brain, that then causes an abnormal in-growth of fine vessels which occurs in response to the lack of blood flow cased by the vessel narrowing. The exact cause of the progressive fibrotic changes in the arterial walls of the cerebral arteries has been the topic of investigation, and no significant inflammatory or infectious pathogens have been found.

It can affect both adults and children. Available evidence appears to indicate that a number of genetic mechanisms, including direct autosomal dominant transmission with incomplete penetrance, and also polygenic mechanisms can render individuals susceptible and that environmental factors also play a role in inducing the arterial that is the basis for moyamoya. Although the exact role of genetics has not been established, the available observations indicate that genetic susceptibility appears to play a major role and environmental factors may trigger the onset of the disease in susceptible patients.

Diagnosis

Severe headaches , seizures or stroke-like symptoms can be the first clinical signs of the disease (CT image A) . A diagnosis of Moyamoya is confirmed with a cerebral angiogram (B arrow shows site of moyamoya disease) –a medical imaging study used to visualize the inside of blood vessels in the brain.

A number of other imaging tools are used to lead to this diagnosis, including:

- CT, CTA or MRI scans showing detailed inner structures of the brain

- Doppler ultrasound, including transcranial Doppler that measures blood flow velocity

- Brain blood flow studies using various tools, including SPECT (single photon emission computerized tomography) that show how blood flows to tissues

Natural History

Most natural history studies of moyamoya disease have been retrospective in nature and limited to small groups of patients. Many of the studies published have separated pediatric and adult patients. Several studies were performed on pediatric patients who were treated conservatively, and have recorded the development of subsequent clinical events. Kurokawa et al reported that about 80% of pediatric patients followed out for 5 years without surgical treatment developed subsequent ischemic or hemorrhagic symptoms.

In adults, the natural history studies to date have indicated that the prognosis is poor for those symptomatic adults treated conservatively without surgery. Most studies have reported some patients where one hemisphere is treated surgically and the other was followed, or mixed groups where some patients were treated with surgery and others were not. Kuroda et al have reported a series of Japanese patients followed over a long period of time where some patients were not treated with surgery. Disease progression occurred in 15 of the 86 non-operated hemispheres (17.4% per hemisphere) or in 15 of 63 patients (23.8% per patient) during the mean 6 year follow-up period. Occlusive arterial lesions progressed in both anterior and posterior circulations, in both symptomatic and asymptomatic patients, and in both bilateral and unilateral types. Eight of 15 patients developed ischemic or hemorrhagic events related to disease progression.

Prevention

One of the current controversies in managing moyamoya patients is regarding the degree of intervention which is appropriate when patients have presented with vascular changes which are limited to one cerebral hemisphere. According to established criterion, these patients would be considered as having a diagnosis of probable moyamoya disease and are sometimes referred to as having moyamoya syndrome. Smith et al reviewed the clinical and imaging records of a series of primarily pediatric patients with moyamoya syndrome who presented with unilateral disease and underwent cerebral revascularization surgery using pial synangiosis, or EDAS, on the affected side. During the follow-up period, 10 (30%) of 33 patients with unilateral findings, progressed to bilateral disease as evidenced by appearance of moyamoya changes in the previously unaffected hemisphere. The mean time until disease progression was 2.2 years (range 0.5–8.5 years). Certain factors were associated with progression including contralateral abnormalities on initial angiography, previous history of congenital cardiac anomaly, cranial irradiation, Asian ancestry, and familial moyamoya syndrome. It was therefore recommended that pediatric patients with known unilateral disease should undergo continued monitoring by diagnostic testing at regular intervals.

Treatment

Talk with your doctor about the best treatment plan for you. Options include:

Medical Treatment

A number of medical treatments have been tried for patients with moyamoya. Antiplatelet agents, most commonly aspirin, are routinely used for patients presenting with stroke symptoms with the rationale that blood clots in the cerebral arteries are commonly observed. Anticoagulation using certain drugs is not commonly used and may be harmful due to the propensity for intracranial bleeding in moyamoya. Other medications including vasodilators, anticonvulsants, and fibrinolytics have also been used but no controlled trials have provided strong support for clinical effectiveness of any medications.

Surgical Treatment

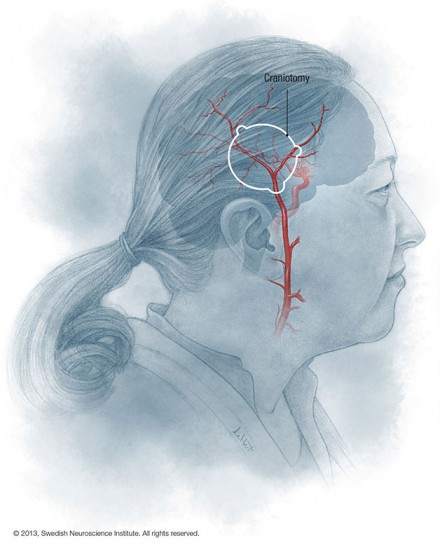

There are two types of revascularization surgery that are now practiced for the treatment of a moyamoya disease and are termed indirect and direct revascularization.

Indirect revascularization

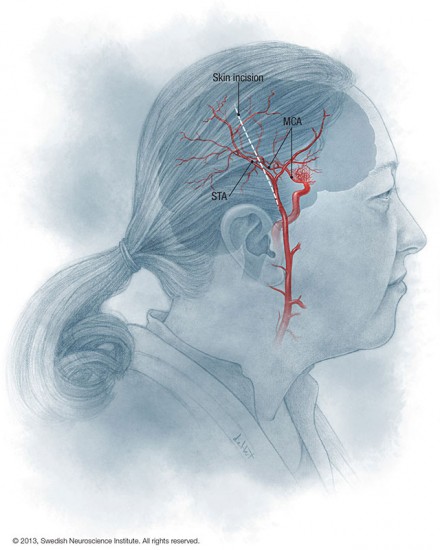

Indirect revascularization involves placing vascularized tissue fed by the external carotid system on to the surface of the brain to allow collateral networks to form and reroute blood flow around the obstructed vessels at the base of the brain.

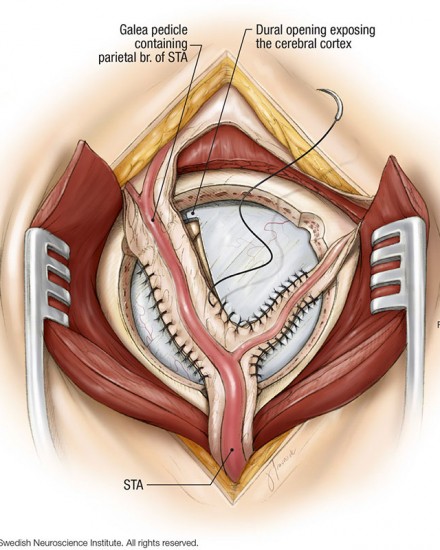

A number of different tissues have been proposed and tried including muscle, omentem, galea, and dura . The most commonly practiced technique currently is termed encephaloduroarteriosynangiosis where the superficial temporal artery is kept flowing and dissected along with vascularized tissue which is then sewn into an opening in the dura and is placed in contact with the cerebral cortex .

This procedure is favored in most centers for pediatric patients due to the small size of the vessels which make direct anastomosis difficult. Indirect techniques are also utilized in adults and can be useful when the donor or recipient vessels are of insufficient size to allow direct anastomosis.

Direct revascularization

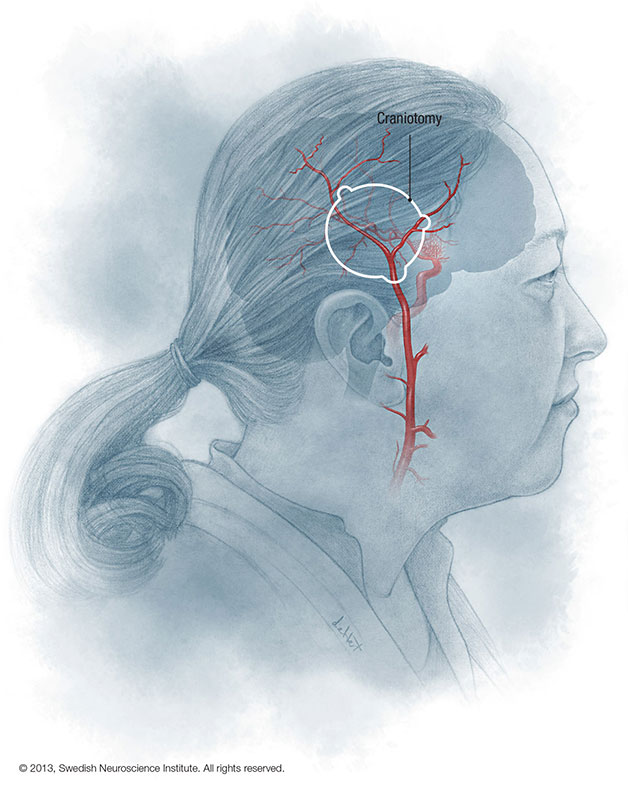

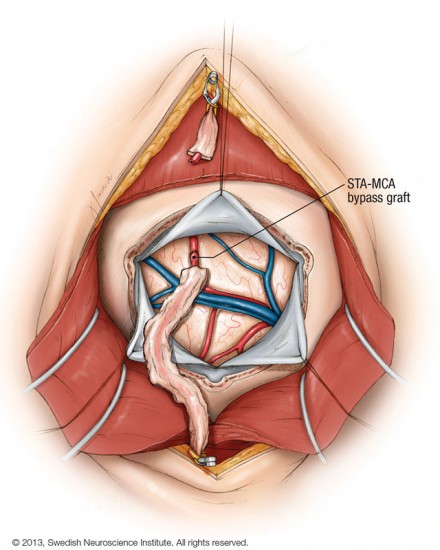

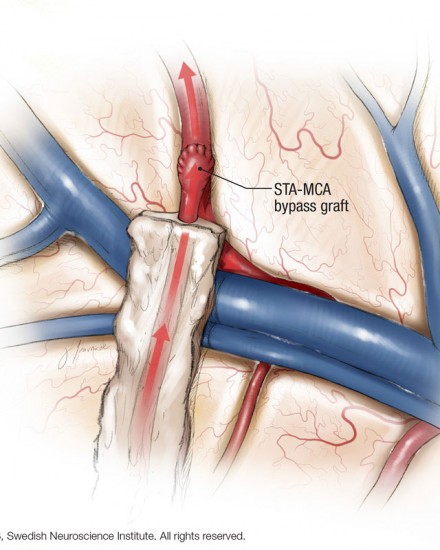

The second treatment is termed direct revascularization, where a direct microvasular anastomosis between the extracranial and intracranial vessels is performed.

The most common procedure performed is a direct superficial temporal to middle cerebral artery bypass using a microvasular suture technique. A microvasular anastomosis technique has also been described for direct anastomosis of the superficial temporal to middle cerebral artery in moyamoya patients.

In cases where these arteries are not suitable other direct vascular anastomosis techniques have been employed using other arteries, or vein grafts. The rationale for this treatment is to allow the more rapid development of collateral vessels to ischemic portions of the brain to prevent recurrent TIAs and/or stroke. Several comparison studies between the direct and the indirect techniques have been performed. In patients with reduced CBF, the direct procedure is often more effective for a more rapid increase in blood flow to the affected brain region.

Video

David Newell, M.D. talks about moyamoya disease, who it affects, and how it’s treated.

Video Transcript

Moyamoya disease is a disease of the brain and blood vessels where the arteries become severely narrow as they enter the brain from the base of the skull.

The symptoms of moyamoya are most commonly transient ischemic events or transient events of numbness, weakness, and speech disturbance. They can occur eposodically and then progress even to a full blown stroke if the condition is not recognized and treated properly. The typical demographic is a young woman with an unexplained stroke that doesn’t have a lot of risk factors for stroke.

Moyamoya was first described in Japan and it has been noted to be more common in Asian populations. The moyamoya refers to a puff of smoke. That’s the Japanese word for puff of smoke, and when you get an angiogram or an injection of the blood vessels, these fine vessels that form in response to the larger disease vessels that start to block off appears as a puff of smoke or a small, fine nest of vessels that forms to try to reroute the blood around the blockage in the arteries.

One of the treatments for moyamoya disease is simple aspirin therapy because we want to thin the blood out to prevent it from clotting in these narrowed vessels.

The two surgical treatments are called direct and indirect bypass procedures. And we take a vessel called the superficial temporal artery, which is an artery in the scalp, and hook that up to some vessels on the surface of the brain. Now we can do a direct anastimosis or a direct connection, similar to a heart bypass procedure, where we sew the vessels together and provide a route for the bloodflow. If the blood vessels are too small or not amenable to that procedure we can do what’s called an indirect procedure where we lay the vessel from the scalp on the surface of the brain and the vessels from the scalp eventually grow in and provide connections in to the brain vessels. That takes longer for that to occur, typically three to six months for that to occur in a major way. So the direct bypass is preferred if it can be done technically because it provides an immediate increase in blood flow to the brain.

In most patients the bypasses have a good long term effectiveness or longevity. When we look at the bypasses over time, if there’s blood demand, those vessels often enlarge quite a bit to even reach the size of the original arteries that were blocked off. And we’ve studied a number of patients over time and repeated their imaging and found that the vessels in most patients do stay open and continue to provide blood flow around the diseased arteries.

There are small risks to the surgery just like any surgery, which include small risk of infection, fluid leakage, a very small risk of stroke or brain adema, but most patients do extremely well and the patency rate or the rate that the bypasses stay open is quite high. It’s over ninety percent in these patients.

At Swedish Neuroscience Institute we have an active program to treat moyamoya patients. We have a large experience in treating them. We utilize special anesthetic techniques, including cooling the patient during the surgery to prevent any reduction in blood flow and there’s a team that’s done a lot of these bypasses and they’re very, very good at it.